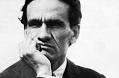

I began to study Portuguese as an optional special subject, in my second year at Oxford. The Portuguese tutor in literature was Tom Earle, and it was he who first introduced me to the poetry of Fernando Pessoa, the colossus of 20th Century Portuguese poetry. Pessoa spent his early childhood in Durban and grew up completely bilingual. He wrote a number of poems in English, notably a sequence of sonnets in the Shakespearean mode. But he is far better known for his poetry in Portuguese.

I began to study Portuguese as an optional special subject, in my second year at Oxford. The Portuguese tutor in literature was Tom Earle, and it was he who first introduced me to the poetry of Fernando Pessoa, the colossus of 20th Century Portuguese poetry. Pessoa spent his early childhood in Durban and grew up completely bilingual. He wrote a number of poems in English, notably a sequence of sonnets in the Shakespearean mode. But he is far better known for his poetry in Portuguese.

Pessoa (his surname means ‘person’ in Portuguese) is famous for having written under the guise of around seventy-five heteronyms. Far more than simple pseudonyms, Pessoa imagined entirely different personae for these fragments of personality within himself and described the experience of being possessed by the different characters at different times and being driven to write in a style markedly peculiar to each individual.

Below, I have chosen to translate poems written by four of these heteronyms: Pessoa himself, Ricardo Reis, who wrote odes in a more classical style, Alberto Caiero and Álvaro de Campos. The selection is insufficient to give anything more than a taste of Pessoa’s craft, but interested readers will find plenty of information online to sate their curiosity.

In the end I was not able to complete my special subject, but the phenomenon of Fernando Pessoa has been with me all my life, and his poetry a constant source of pleasure.

It’s raining. There’s silence

It’s raining. There’s silence, because the rain itself

Makes no noise but falls gently.

It’s raining. The sky sleeps. When the soul’s a widow

Which you can’t know, feelings are blind.

It’s raining. Who I am (my being) I disown. . .

So calm is the rain that drifts in the air

(there seem to be no clouds) so that it seems

Not to be rain but a whisper

That of itself, with a whisper, forgets it exists.

It’s raining. No wish to do a thing. . .

No hovering wind, no sky that I can sense

It’s raining far far away and indistinctly,

Like a certainty that deceives us,

Like some big desire that lies in our face.

It’s raining. I feel nothing inside. . .

Fernando Pessoa

*

Come sit with me, Lydia, by the river’s edge

Come sit with me, Lydia, by the river’s edge.

Quietly watch it flow and understand

That life goes on, and our hands aren’t clasped.

(Let’s clasp hands.)

Then think, as children who have grown up, that life

Flows by, never lasts, leaves nothing, never returns,

But flows on into a far-off sea, at the foot of the Fado,

Beyond the gods.

Let’s unclasp hands because no point in us tiring.

Enjoy it or not, we flow on like the river.

Better to understand how to move silently with the flow

Without major upsets.

Without love, nor hatred, nor passions that cry out,

Nor longings that over-excite the eyes,

Nor cares, for regardless of cares the river flows on,

Will always run down to the sea.

Let us love without fuss, thinking that we could,

If we wanted, exchange a kiss, an embrace, a caress,

But it’s better just to sit side by side

And listen and watch as the river flows by.

Let’s pick flowers, you gather them and keep them

In your lap, and let their scent soften the moment

This moment when at peace we have no beliefs,

Innocently decadent pagans.

At least, if once there were shades, you should remember me

But not let my memory burn or hurt or move you,

Because we never clasped hands, nor ever kissed

Were never more than children.

And should you hand the dark boatman his coin before me,

There’ll be nothing to bring me pain when I remember.

Gently my memory will recall you thus – by the river’s edge,

My own sad pagan with flowers in your lap.

Ricardo Reis

*

That lady has a piano

That lady has a piano

Which is nice but not the flow of rivers

Nor the murmur the trees make. . .

Why must one have a piano?

It’s better to have ears

And to love Nature.

If I could crack the whole earth

If I could crack the whole earth

And feel it had a palate,

I’d be happier for a moment. . .

But I don’t always want to be happy.

You have to be occasionally unhappy

In order to be natural . . .

It’s not all sunny days,

And the rain, after much drought, is required.

So I treat unhappiness and happiness the same

Of course, as one not surprised

That there are mountains and plateaux

And there are rocks and grass. . .

What’s required is to be natural and calm

In happiness or unhappiness,

Feel like someone who notices,

Think like someone who walks,

And when you’re dying, remember that the day dies,

And that the sunset is beautiful, beautiful the night that remains. . .

So it is and so be it. . .

Alberto Caeiro

*

Magnificat

When will this inner night, the universe, pass

And me, my soul, have its day?

When will I wake from being awake?

I don’t know. Impossible to stare

As the sun on high glares.

The stars shimmer coldly

And can’t be counted.

The heart beats so remotely

And can’t be heard.

When will this theatreless drama

Or this dramaless theatre pass

So I can go home?

Where? How? When?

Cat staring at me, eyes agog with life, what do you hold deep inside?

He’s the one! He’s the one!

Like Joshua he’ll order the sun to stop, and I’ll awake;

And then it’ll be day.

Smile, as you sleep, my soul!

Smile, my soul, it’ll be day!

Álvaro de Campos

I wake at dawn. Gayle is still fast asleep. My throat is dry. I reach for the glass of water on the bedside cabinet and drain it. My hands are shaking. I put down the glass. Gayle turns over and for a moment her eyes open. She looks at me and smiles. I lean across and kiss her on the forehead. She mutters something in a sleepy drawl which I cannot understand. I pull the covers up around her shoulders. You go back to sleep, I say. She smiles again and closes her eyes. I run my fingers through her grey hair. The hair is dry and brittle. Her soft skin is marked now with fine deep lines like a spider web of pain.

I wake at dawn. Gayle is still fast asleep. My throat is dry. I reach for the glass of water on the bedside cabinet and drain it. My hands are shaking. I put down the glass. Gayle turns over and for a moment her eyes open. She looks at me and smiles. I lean across and kiss her on the forehead. She mutters something in a sleepy drawl which I cannot understand. I pull the covers up around her shoulders. You go back to sleep, I say. She smiles again and closes her eyes. I run my fingers through her grey hair. The hair is dry and brittle. Her soft skin is marked now with fine deep lines like a spider web of pain.