PEARL

PEARL

When I say I loved Betty Foster, I mean I loved her, no two ways. She was the best thing that ever happened to me, and when she left it nearly broke my heart. It all fell apart last summer, round about this time. Now I’m sitting out on my porch drinking Budweisers and staring across at her empty home and in that empty home I see nothing but my empty heart and Betty Foster gone away. Over ten months that house has been on the market and far as I can tell not a single potential purchaser has come forward. In this part of Montana real estate just isn’t shifting like it used to. These are hard times. For everyone. I run a small travel firm and believe me, bookings are down by almost a half. So don’t talk to me about economic miracles. These are hard times and we are all depressed. Betty Foster moved—up to Portland, Oregon, I hear—and in her valise she took my heart. Yes sir.

She never loved her husband, Vern. She told me that often enough. Never loved him from day one of their marriage. So why stay with him, I kept asking and she would look at me and say: Because I was brought up to believe that marriage was for keeps and that’s the way I am and I just can’t change. But you don’t love him, I’d say . That’s true, she’d answer me. That’s very true, but I won’t leave him either. It just doesn’t make any sense, I’d say back to her, frustrated and a little petulant and she’d say: So what? Who says life ever has to make sense? And to that I had no answer! Tell you the truth, although I loved her, Betty remained right to the very end a real mystery to me. All I knew was that I loved her and she loved me. And she was the best thing in my life, the very best ever. We were made for each other: how often did we tell each other that? Vern travelled the length and breadth of the country hawking the expert systems he worked on; and while he was away —often for days at a stretch— Betty and I would get together. Occasionally in my house, but mostly in hers. She forced me to take risks when it would have been so easy for her to come across to me! You know sometimes I honestly believed she wanted him to catch us, just to see his reaction, just to see what would happen. But I don’t think Vern ever knew what was going on, and even if he had found out, I’m not so sure he’d have bothered to do anything about it. Vern was a high-flyer and he lived for his work. Incidentally, it wouldn’t have surprised me to learn that he had a string of women tucked away in every major city who kept him company while he was on his sales trips, glamorous women. Betty was beautiful but not in a glamorous way. I always had a hunch Vern —the tall, slim, silent type— was a ladies’ man. With Betty, however, he was cool. Sometimes the two of them would invite me over for drinks at Thanksgiving or Christmas, but I never got the impression he really loved his wife. Betty was a fine woman, but to Vern, it appeared, she was just someone who could guarantee him a change of clothes between trips. When we were alone once I asked Betty: Does he insult you or hit you, does he treat you bad? She laughed. Honestly she laughed outright in my face. Vern hit me? You have to be joking. He’s never laid a finger…he hasn’t the slightest interest in me. Then leave him for Christ’s sake, I’d say. Come live with me. But no, she wouldn’t hear of it. And then when Vern died in a freak accident, sure I was upset for her and naturally I never would have wished anything like that on him, but I thought, this is it, she’ll soon be mine, once she gets over the shock. Instead, she crept away in the dead of night. Portland, Oregon, they say.

There’s a smell of honeysuckle in the air and I can hear the crickets in the long grass. I open another Budweiser and gaze across at Betty’s empty house. Jesus, I can’t take my mind off that house. I still go over sometimes to cut Betty’s grass and weed the front lawn. It’s a way of keeping in touch, at least I feel it is, though something tells me too that Betty’s never coming back. Not an easy feeling to bear, honestly. I can remember saying to her, real exasperated: You don’t mind cheating on your husband that you don’t love anyway but you won’t leave him. You’re going to have to explain that one to me Betty, because the way I see things, we’re playing with different sets of marbles. We have one life only, for God’s sake. Let’s make the most of it. Come on Betty, let’s.

Appears Vern was out driving late one night when a sudden storm blew up. A real hell of a wind. One of those huge billboards—advertising I don’t know what—came crashing down through the windshield. Must have killed Vern outright, the poor bastard. His face. Should have seen what it did to his face, Betty said to me afterwards. You should have seen. It was ghastly. And then a few days later she said: My God, I feel so guilty. It should never have happened. Vern didn’t deserve to die like that. I feel so guilty. And she did, though I tried to reason with her. Nobody should die like that, I agree, I said. But it wasn’t you and it wasn’t us that brought that billboard down, so don’t go blaming yourself. She turned on me, and there was a cool, hard look in her eyes. You think not, she said indignantly. You think we had nothing to do with it? Nothing at all, I said. But I knew I’d lost her. There and then I just knew it. Could see it in those beautiful sad grey eyes of hers. That was the last time we ever slept together. Ten days later the house was closed up, the furniture was put in storage and she was away to Portland, Oregon. And we were truly made for each other.

I know every room in that house, as though it were my own home. And every window. The huge bay window on the ground floor where she would stand and wave across at me. The bedroom window with the curtains still drawn, the rose-coloured chintz behind which we made so much love. Loved her so much. To the point of distraction, and jealousy. Once, I remember, one of those rare weekends Vern was home, I sat up through an entire night —it was a Sunday. I sat here on the porch drinking whisky sours and staring up at that bedroom window while by my side a cassette player softly played over and over the Patsy Cline tapes that Betty and I loved so much. Sat and waited till around midnight their bedroom light was switched on. And then I waited some more and drank some more whisky and felt worse and more heartsick, waiting for the light to go off, which didn’t happen till way after one, me just sitting there, sipping at my whisky, gazing up at that light wondering which part of her he was touching now, and now, and now and how she was responding. And it was as though, I truly felt as though she was being unfaithful to me, that I almost had a right to run out back and fetch my shotgun and then rush across there, burst into that room and put a stop to it once and for all. Following morning, around seven, I heard their front door. Saw her standing there in her night-dress, and a moment later Vern by her side in his business suit, attaché case in hand. I saw her kiss him good-bye, saw him wave as he backed out of the drive, saw her wave back to him as he began to pull away, and when he was gone, saw her look across the road, and seeing me, saw her wave, a gentle wave, and saw her wait for me to wave back, but by then I hadn’t the heart and I saw her eyes fall as she turned back into her house and closed the door. And then I saw too that I understood nothing about Betty Foster except that I loved her and would never understand her.

How come you never married, she asked one afternoon, lying there in that bed, the pink satin sheet pulled up over her breasts, her long brown hair spilling over the pillow. Nobody gets to your age without some sort of damage. What happened to you? I’d just turned fifty-four and Betty and I’d been seeing each other for a couple of years by then. O, I said to her, turning in the bed so that I could stroke her breasts: O I guess I was saving myself, all my life I’ve been saving myself for someone like you. She just burst out laughing. Be serious, she said, can’t you just for once give me a straight answer. But it was a straight answer. I never loved anyone like I loved Betty Foster. I guess she never could quite believe that. Yes, there were others, and sometimes I did draw close and hope and get a sense of magic. But no never, never anyone like Betty.

I’m thinking about her long, smooth legs and the tiny black hairs around her nipples that I used to chew on and of what the two of us used to do in her kitchen, or in the living room in front of the open fire winter times, or the times we took steaming hot baths together, she soaping my back as I soaped her feet and kissed her toes one by one, the things we did. I’m sitting there, thinking these things when I hear a car approaching and I look up and see Bill Douglas’s blue Plymouth hatchback swing around the corner. Bill and I go way back. We were in elementary school together and I love that man as I might have loved a brother had I ever had a brother. He turns in and parks under my car port and jumps out, still in his fishing clothes. In his hand he’s carrying a string of yellow perch. These are for supper, he says, handing me the fish. Four good specimens. Sit yourself down, Bill, I say. Take a beer. I’ll just run these out to the fridge. When I get back, Bill is staring across at Betty Foster’s empty house and sipping at his beer. To Bill, just like to me, that empty house has come to be a kind of heartbreak hotel: just looking at it brings you down. Still no takers, he asks. I shake my head. Bill knows about Betty. You can’t hide a thing like that from your best friend. So how’s tricks, he says. Fine, fine, I say, snapping open another Budweiser. And you? A great day’s fishing, you see the results for yourself. It’s an honest enough answer but an evasive one also. Like me, Bill’s been through the mill recently. His wife Marjorie died just over three months ago: of a brain tumour. I’ve been nursing him ever since. Sometimes it seems like the whole of Montana is in mourning for someone or other. Like nothing lives forever, nothing lasts. Jesus, nothing at all. And he loved her. Every bit as much as I loved Betty. Bill deals in foodstuffs. And sure he’s had his ups and downs like the rest of us. But just about the time he feels he’s getting out of the woods, Marjorie goes and dies on him. Right when they were making plans for the great European tour. And it’s aged him. He’s lost hair and what’s left is greyer and his face has gone slack and pale and I know he’s struggling, dear God I know that feeling. Whenever his beer is out of his hand I catch him stroking his wedding ring. Little things like that. And I know that for some pain there simply is no cure. Betty Foster.

Smell that honeysuckle, Bill says taking in a deep breath, just smell that smell. And I know that when he says that he’s smelling something else because I’m smelling it too. His eyes are on Betty’s house, but his heart is elsewhere. Beautiful smell, I say, and he nods but does not look at me. He nods and sighs and tips back his can of beer and then takes another deep breath. Honeysuckle.

He offers to help me clean the fish but I say: No, Bill, your work is done for the day. Today I’m going to look after you. You just sit there and take it easy. I’ll have it done in no time. Now he does smile. Brotherly love just isn’t the same, but it can help when that’s all there is.

About ten minutes later I hear Bill calling through to me. I walk out to the porch with a cloth in my hands. Bill points to the small removal truck now stationed in front of Betty Foster’s place. The removal man has the back of the truck open and standing next to him there’s a woman. I drape the cloth over the railing and sit down. Bill opens another beer and hands it to me. Both of us are concentrating on the woman. The way I see it, she’s about forty-five, average height and trim figure—trim for forty-five, though Betty was a bit stouter and none the worse for that. She’s wearing a black cardigan and black pants. The removal man jumps up into the back of the truck and a moment later he emerges with the end of a table, a dining-table. The woman takes hold of the end of it and the man climbs back in the truck and between them they manoeuvre it all the way out and then up the sloping path and into the house. Bill looks at me as they disappear. My hands are still covered in fish scales, tiny flakes of silver. A moment later the two of them come out of the house. The man hands down four dining-chairs which the woman stacks by the side of the truck. Then together they take in the chairs. Next, what looks like an antique chaise longue. As the man is easing it out of the truck the woman loses her grip and the chaise drops to the ground on one corner. There is the sound of splintering wood as one of the legs snaps. Bill and I hurry across the road to see if we can help. It occurs to me that we could have offered earlier, before the damage was done.

Let me tell you, it’s a strange feeling to be sitting in Betty’s living room surrounded by all this chaos created by someone else’s furniture and boxes and bits and pieces. The air is stale, like in a mausoleum but without the body. The carpets are still in place, the fixtures too and I can’t help thinking just how utterly provisional our lives really are. What you thought would last forever is here today and gone tomorrow. Betty Foster, I loved you!

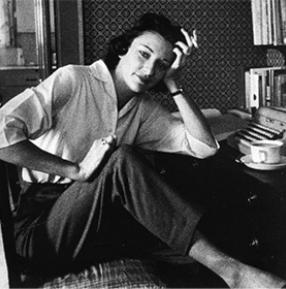

Pearl. Her name is Pearl. She is pacing up and down the living room making mental notes of where to position her furniture. Bill is fussing with the broken leg of the chaise longue. He is twisting it back and forth, trying to evaluate the damage. He shows it to me for a second opinion, but I have to shrug my shoulders; I know nothing about carpentry. Deciding that the job is within his powers, he offers to take the chaise away and return it once it’s fixed. Pearl seems a little nervous about the whole business and she hesitates before finally accepting. She smiles at Bill and it’s a warm smile and it casts a warm glow on Bill’s face. She’s pretty. Prettier than I first thought. An oval face and chestnut hair which hangs in neat delicate curls. Brown eyes and soft skin, her skin looks soft, as though she’s spent a lifetime taking care of it.

Bill and I carry the chaise longue out of the house and over to my place. He opens the back of the Plymouth, pushes the fishing gear to one side and together we get the chaise inside. Pearl hands Bill the broken leg which he places in the back also. He then locks up. I leave them sitting out on the porch while I fetch the wine. I take it out on a tray with three glasses. Do you mind red wine with your fish, I ask Pearl. Not at all, she says. Wine is wine. Red is fine. She takes the glass in her left hand and for the first time I notice her long, pale fingers, the warm pink glow of blood beneath her nails, and no ring of any sort.

Bill can’t take his eyes off her and all through the meal he’s stealing glances like a kid in high school on his first date. And I’m thinking, Betty Foster, I truly loved you, why did you leave me? But I’m also thinking Pearl is a nice name, and Pearl is a charming lady, and Bill is my best friend. You caught this fish, she says to him. He smiles. You caught this fish? This fish is magnificent. Best fish I’ve eaten in years, best in years. And Bill smiles proudly as she rolls a piece of fish around her palate.

So, tell us about yourself, I say to Pearl when the dishes have been cleared away. She lowers her head. O, she says, what’s to tell? Beyond her, across the street, a light is burning in Betty Foster’s house. The crickets have long gone quiet and there’s just a hint of honeysuckle in the air now. Slowly she raises her eyes and looks first at Bill who a while back seemed to slip into a world of his own—and I know where that is—and then with those deep, dark brown eyes of hers she looks at me—and I’m thinking of Betty Foster’s breasts—and I look back into her eyes, soft and smiling and just a little bit sad and I know that she is right. What is there to tell?

© John Lyons, 1992