“I remember very well the impression I had of Hemingway that first afternoon. He was an extraordinarily good-looking young man, twenty-three years old. It was not long after that that everybody was twenty-six. It became the period of being twenty-six. During the next two or three years all the young men were twenty-six years old. It was the right age apparently for that time and place.”

“So Hemingway was twenty-three, rather foreign looking, with passionately interested, rather than interesting eyes. He sat in front of Gertrude Stein and listened and looked.”

“Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway talked then, and more and more, a great deal together. He asked her to come and spend an evening in their apartment and look at his work. Hemingway had then and has always a very good instinct for finding apartments in strange but pleasing localities and good femmes de ménage and good food. This his first apartment was just off the place du Tertre.”

“We spent the evening there and he and Gertrude Stein went over all the writing he had done up to that time. He had begun the novel that it was inevitable he would begin and there were the little poems afterwards printed by McAlmon in the Contract Edition. Gertrude Stein rather liked the poems, they were direct, Kiplingesque, but the novel she found wanting. There is a great deal of description in this, she said, and not particularly good description. Begin over again and concentrate, she said.”

Extracts from Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

I became fascinated by the writings of Gertrude Stein after reading The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in which she assumed the persona of her partner, Alice, to tell her own life story. There is nothing straightforward about Stein’s writings, many of which represent an insurmountable challenge to most readers, not excluding, at times, myself. Nevertheless, it is always worth persisting with genius.

Over the years I have learnt to read her texts and discovered that to do so, one really has to read them out aloud to capture her breath, much as one has to do with Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Stein was a very close friend of Picasso and Matisse and Cézanne and other artist contemporaries in the early part of the 20th century, and the salon which she held at her home, 27 rue de Fleurus, in Paris, was frequented by many of the leading avant garde writers from Europe and the United States. It was supposedly Gertrude Stein who coined the term ‘the Lost Generation’ referring to Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, among others.

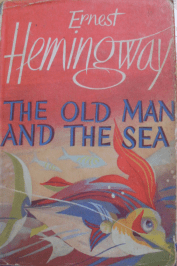

The story I am posting today, although entirely fictitious, was inspired by my reading of the relationship Gertrude Stein had with Ernest Hemingway as hinted at in the quotations above.

At one point in the Autobiography, she speaks of her agreement with the writer, Sherwood Anderson in these terms: “But what a book, they both agreed, would be the real story of Hemingway, not those he writes but the confessions of the real Ernest Hemingway. It would be for another audience than the audience Hemingway now has but it would be very wonderful.”