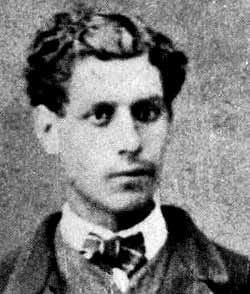

The extract below from Proust’s monumental novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, recounts the infamous scene in which the Duke and Duchess de Guermantes, impatient to leave for a grand evening dinner, can barely find time to talk to their dear friend Charles Swann, who has little time to live.

The extract below from Proust’s monumental novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, recounts the infamous scene in which the Duke and Duchess de Guermantes, impatient to leave for a grand evening dinner, can barely find time to talk to their dear friend Charles Swann, who has little time to live.

In this incident, Proust captures the petty, selfish, and superficial side of those occupying the highest circles of the Parisian aristocratic world.

The red shoes – Marcel Proust

“Listen, Basin, I’d like nothing better than to follow you to the moats of Vincennes, or even to Taranto. And by the way, my dear Charles, that’s exactly what I wanted to tell you when you were telling me about your St. George’s in Venice, you see Basin and I, are thinking of spending next spring in Italy and Sicily. If you were to come with us, just think what a difference it would make! I’m not just thinking of the pleasure of seeing you, but imagine, after all you’ve told me so often about the times of the Norman Conquest and ancient times, imagine what a trip like that would become if you came with us! I mean to say that even Basin, I mean, Gilbert, would benefit from it, because I feel that even the claims to the throne of Naples and all that sort of thing would interest me if they were explained by you in old Romanesque churches or in tiny villages perched on hills like primitive paintings. But now then, let’s take a look at your photograph. Open the envelope,” the Duchess said to a footman.

“Please, Oriane, not tonight; you can look at it to-morrow,” implored the Duke, who had already been making signs of alarm to me on seeing the huge size of the photo.

“But I enjoy looking at it with Charles,” said the Duchess, with a smile at once archly sensuous and psychologically subtle, for in her desire to be friendly to Swann she spoke of the pleasure which she would have in looking at the photo as though it were the pleasure a person who is unwell feels he would find in eating an orange, or as though she had managed to combine a jaunt with her friends with giving information to a biographer as to some of her favourite pursuits.

“Very well, he can call on you again with that in mind,” declared the Duke, whom his wife was obliged to obey. “You can spend three hours poring over it, if that’s what amuses you,” he added ironically. “But where are you going to stick such a monstrous whatnot?”

“Why, in my room, of course. I want to have it in my sight.”

“Oh, just as you please; if it’s in your room, I’ll probably never get to see it,” said the Duke, without thinking of the revelation he was so blithely making of the negative state of his conjugal relations.

“Very well, you will take it out with the greatest care,” Mme. de Guermantes told the servant, multiplying her instructions out of politeness to Swann. “And see that you don’t crumple the envelope, either.”

“So we must respect even the envelope!” the Duke muttered to me, throwing his arms up. “But, Swann,” he added, “I, who am only a poor married man and thoroughly prosaic, what I really admire about this is how you managed to find an envelope of that size. Where did you dig it up?”

“Why, at the studio of the photographer who’s constantly sending out these sort of things. But the man’s a fool, for I see he’s written on it ‘The Duchess de Guermantes,’ without putting ‘Madame.’”

“I’ll forgive him for that,” said the Duchess nonchalantly; then, seeming to be struck by a sudden idea which enlivened her: “Well you haven’t said whether you’ll come to Italy with us?”

“Madame, I’m afraid that really won’t be possible.”

“Oh well! Mme. de Montmorency has all the luck. You accompanied her to Venice and Vicenza. She told me that with you one saw things one would never see otherwise, things no one had ever thought of mentioning before, that you showed her things she’d never dreamed of, and that even in the well-known things she’d been able to appreciate details which without you she might have passed by a dozen times without ever noticing. Obviously, she has been more highly favoured than we are to be…. You’ll take the big envelope with Mr Swann’s photograph,” she said to the servant, “and you’ll deliver it, courtesy of me, this evening at half past ten to the home of Mme. la Comtesse Molé.”

Swann burst out laughing.

“I’d like to know, all the same,” Mme. de Guermantes asked him, “how, ten months beforehand, you can tell that a thing will be impossible.”

“My dear Duchess, I’ll tell you if you insist, but, first of all, you can see that I am very ill.”

“Yes, my dear Charles, I don’t think you look at all well. I’m not happy with your colour, but I’m not asking you to come with me next week, I’m asking you to come in ten months. In ten months one has time to get oneself cured, you know.”

At this point a footman came in to say that the carriage was at the door. “Come on, Oriane, horsey up,” said the Duke, already pawing the ground with impatience as though he were himself one of the horses that stood waiting outside.

“Very well, in a word tell me what’s to stop you coming to Italy,” the Duchess asked as she rose to bid us good-bye.

“But, my dear friend, it’s because I shall have been dead for several months. According to the doctors I consulted last winter, this thing I’ve got—which may, for that matter, carry me off at any moment—won’t in any case allow me more than three or four months to live, and even that is a generous estimate,” Swann replied with a smile, while the footman opened the glazed door of the hall to let the Duchess out.

“What on earth are you saying?” cried the Duchess, pausing for a moment on her way to the carriage, and raising her fine eyes, their melancholy blue clouded by uncertainty. Caught for the first time in her life between two such different obligations as getting into her carriage to go out to dinner and showing pity for a man who was about to die, she could find nothing in the code of conventions that indicated the correct ruling to follow, and, not knowing which to choose, felt it better to make a show of not believing that the latter alternative need be taken seriously, in order to follow the first, which at the moment demanded less effort on her part, and thought that the best way of resolving the dilemma would be to deny that any existed.

“You jest,” she said to Swann.

“It would be a quite charming jest,” he replied ironically. “I don’t know why I am telling you this; I’ve never said a word to you before about my illness. But since you asked, and as now I may die at any moment… But above all, I don’t want you to be late; you’re dining out, remember,” he added, because he knew that for other people their own social obligations took precedence over the death of a friend, and he was able to put himself in her place thanks to his instinctive politeness. But the Duchess’s politeness enabled her also to perceive in a vague way that the dinner to which she was going must count for less to Swann than his own death. And so, while continuing on her way towards the carriage, she let her shoulders droop, saying: “Don’t worry about our dinner. It’s of no consequence!” But this put the Duke in a bad humour, who exclaimed: “Come on, Oriane, don’t stop there chattering like that and swapping tragic stories with Swann; you know very well that Mme. de Saint-Euverte insists on sitting down to table at eight o’clock sharp. We need to know what you want to do; the horses have been waiting a good five minutes. I beg your pardon, Charles,” he continued, turning to Swann, “but it’s ten to eight already. Oriane is always late, and it’ll take us more than five minutes to get to old Mme. Saint-Euverte’s.”

Mme. de Guermantes strode towards the carriage and uttered a final farewell to Swann. “You know, we can talk about this another time; I don’t believe a word you’ve been saying, but we must discuss it calmly. I expect they gave you a dreadful fright, come to lunch, whatever day you like” (with Mme. de Guermantes, lunches always resolved everything), “you’ll let me know the day and time,” and, lifting her red skirt, she set her foot on the step. She was about to get into the carriage when, seeing this foot exposed, the Duke cried in a terrifying voice: “Oriane, what were you thinking, you poor creature? You’re still in your black shoes! With a red dress! Go upstairs quickly and put on your red shoes, or rather,” he said to the footman, “tell the lady’s maid to bring down a pair of red shoes at once.”

“But, my dear,” replied the Duchess gently, annoyed to see that Swann, who was leaving the house with me but had stood back to allow the carriage to pass out in front of us, could hear, “since we’re late.”

“No, no, we’ve plenty of time. It’s only ten to; it won’t take us ten minutes to get to the Parc Monceau. And, after all, what would it matter? If we turned up at half past eight they’d have to wait for us, but you can’t possibly go there in a red dress and black shoes. Besides, we shan’t be the last, I can tell you; there’s the Sassenages, and you know they never arrive before twenty to nine.”

The Duchess went up to her room.

“Well,” said M. de Guermantes to Swann and myself, “us poor, down-trodden husbands, people laugh at us, but we are of some use all the same. Had it not been for me, Oriane would have been going out to dinner in black shoes.”

“It’s hardly an eyesore,” said Swann, “I’d noticed the black shoes and they didn’t bother me in the least.”

“I’m not saying you’re wrong,” replied the Duke, “but it looks better for them to match the dress. Besides, you needn’t worry, she’d no sooner have got there than she’d have noticed them, and I’d have been obliged to come home and fetch the others. I’d have had my dinner at nine o’clock. Good-bye, you youngsters,” he said, gently pushing us away, “hurry along, before Oriane comes back down. It’s not that she doesn’t like seeing the two of you. On the contrary, she’s too fond of your company. If she finds you still here she’ll start talking again, she’s worn out already, she’ll get to the dinner table quite dead. Besides, I tell you frankly, I’m starving. I had a wretched lunch this morning when I got off the train. There was a hell of a béarnaise, I admit, but despite that I shan’t be at all sorry, not at all, to sit down to dinner. Five to eight! Oh, women, women! She’ll give us both indigestion. She’s not quite as tough as people think.”

The Duke felt no compunction speaking this way of his wife’s ailments as well as his own to a dying man, because these ailments interested him more, seemed more important to him. And so whether simply out of good breeding and good humour, after politely leading us out, he bellowed in a stage voice from the porch to Swann, who was already in the courtyard: “Now look here, don’t let yourself be knocked back by the doctors’ nonsense, damn them. They’re asses. You’re as sturdy as the Pont Neuf. You’ll bury us all!”

(Translation by John Lyons)

See also

Marcel Proust – The intermittences of the heart

Madeleines – A Proustian experience

The extract below from Proust’s monumental novel,

The extract below from Proust’s monumental novel,